Lunar time keeping with a sextant and a sliderule

Intro to Lunars

Most of this is based on Frank Reed's "Lunars are Easy" page and Wendel Brunner's "Longitude by the method of lunar distance".

While the development of the chronometer during the Longitude Prize is usually cited as the first means for sailors to calculate their longitude, it is also possible to compute the current time in Greenwich using the distance from the Moon to the Sun or other stars. This can be used to adjust a less accurate clock, which was important when a Harrison H4 Regulator cost four million pounds (after inflation adjustments). And since a sailor "never goes to sea with only one clock", (Segal's law), that adds up to real money -- the HMS Beagle had twenty two since several were expected to break during the trip.

Roughly speaking the Sun moves across the sky at 15° per hour, 360° per day, while the Moon is slightly slower at around 14°19' per hour. This means that each day after a new moon (when the Sun and the Moon are roughly at the same global hour angle), the Moon's GHA will be ~17° behind the Sun. ~14 days later they will be 180° apart and the moon will be full. After ~29 days the two will be close to alignment again and the moon will be new.

If you can measure the angular distance between the Sun and the Moon, then you can tell how far into this cycle they are. The Nautical Almanac Lunar Distance Tables contain this distance for every hour of every day of the year. So in theory, tilt your sextant and adjust the angle to bring the Sun to the Moon, read the distance from the scale, make a few corrections, and consult the almanac for the current day to find the hour that the moon would be at that distance and now you know what time it is.

As with everything involved with celestial navigation, there are lots of caveats and those corrections can be quite involved...

Example

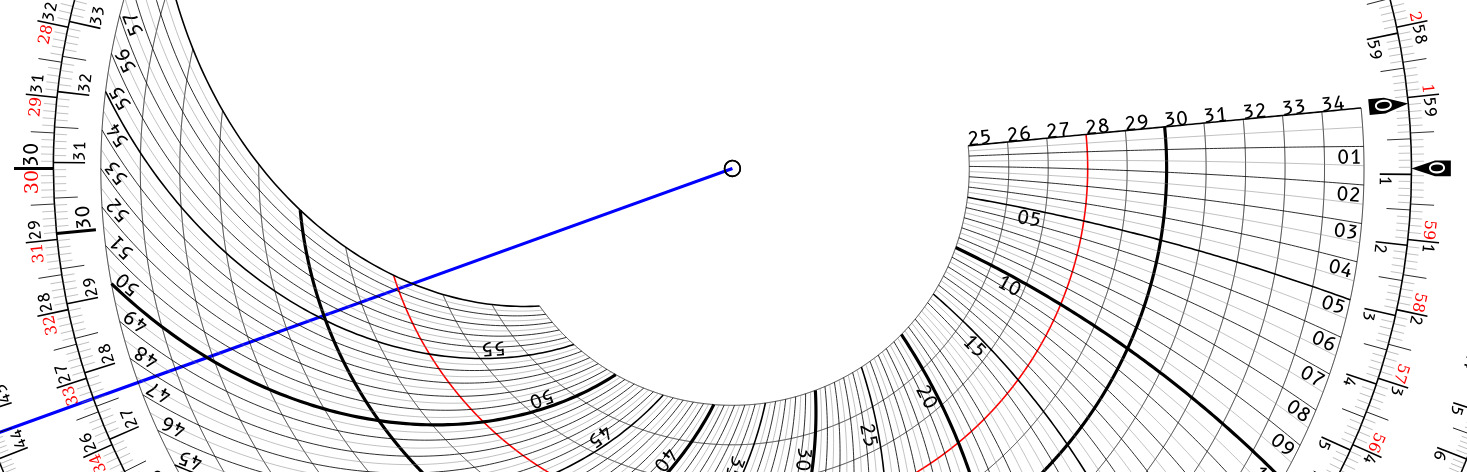

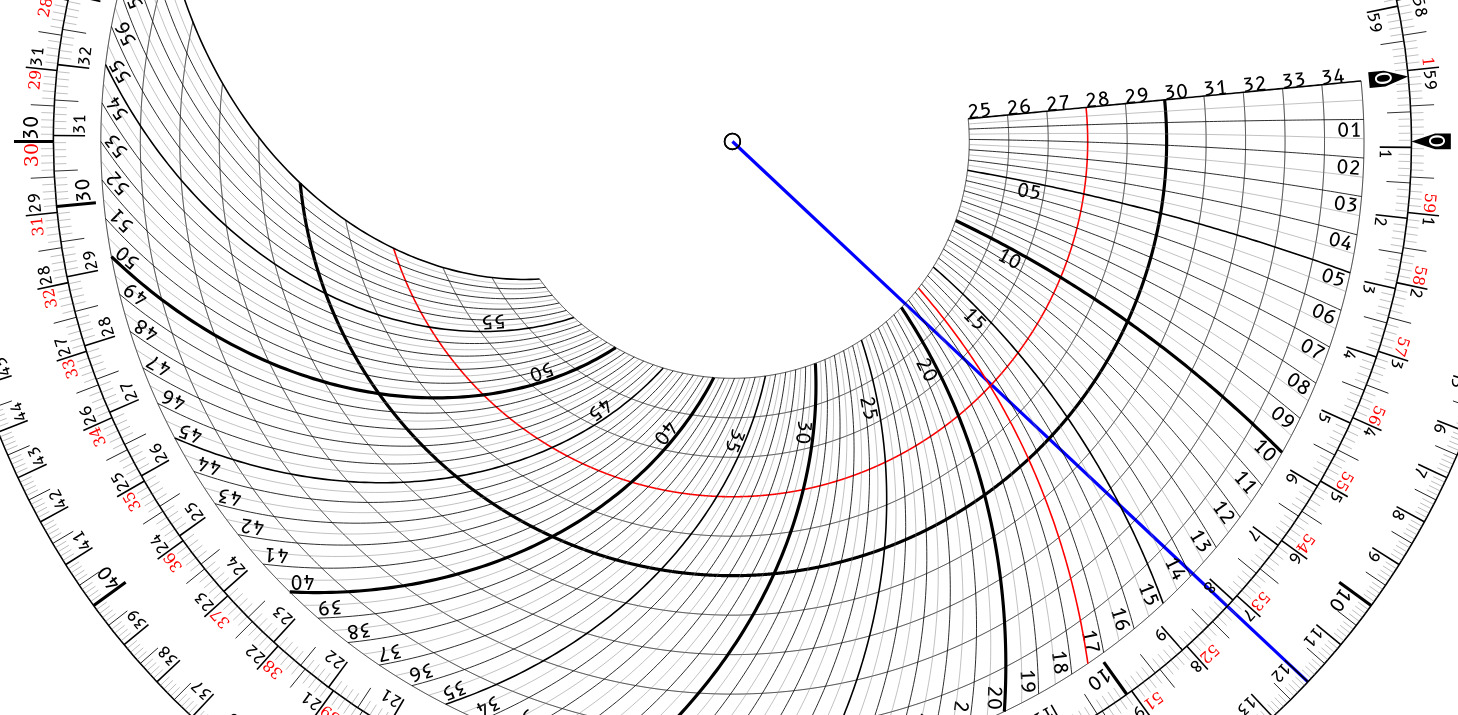

For this example I'm reusing the data from Reed's "Lunars are easy" so that I can demonstrate my methods, which are slightly different from his. This is also an introduction to my lunar slide rule, shown above.

The measurements that Frank published are:

- Observation: 2004-04-26

- Height of eye: 3m

- Moon upper limb: 45° 46.8' (20:09 GMT)

- Sun lower limb: 47°49' (20:11 GMT)

- Moon-Sun Near: 80°9.3' (20:16 GMT)

- Moon upper limb: 47° 13.8' (20:17 GMT)

The almanac for that date says:

- Sun Semidiameter: 15.9'

- Moon Horizontal Parallax: 54.7

- Lunar Distance 20:00 GMT: 79°59.1'

- Lunar Distance 21:00 GMT: 80°26.7'

The first step is to compute the Moon's semidiameter for the current observation, which is influenced by the amount of parallax due to how close the moon is to us. All of our calculations are done from the center of the earth, but we're viewing it from the surface. The formula for it is:

The parallax side of the slide rule can assist with this measurement; set the pointer to zero on the outer, rotate the inner to the small sine adjustment, then rotate the pointer to the HP on the outer to read the minutes of semidiameter.

- Moon's semidiameter is 15.1'.

Now the Lunar Distance needs to be adjusted to add both the semi-diameter of the sun and the moon (since it was measuring the near sides of each and we want need from center-to-center) The slide rule helps with this as well; to be written.

- Observed Lunar Distance 80°40.3' = 80°9.3' + 15.9' + 15.1'

Frank has two moon heights, so his estimate of the height for the time of the lunar distance measurement is interpolated between them:

- Moon upper limb: 47°0.5' (20:16 GMT)

I'm not sure where his Sun height came from, he says it was probably about a degree and a half lower by this time, and I think the assumes it is 47°0' at the time of measurement.

Using the sun wheel we can adjust these for the semi-diameter and height of eye calculations. Frank uses an approximation of +12' for lower limb and -20' for upper limb, which is close to what the sun wheel gives us:

- Height observed Sun: 47°12.8' = 47°0.0' + 15.9' - 3.1'

- Height observed Moon: 46°42.3' = 47°0.5' - 15.1' - 3.1'

TODO: figure for this triangle.

Now the angle between them is computed using the spherical triangle. TODO: show how to do this on the nav wheel

- Sun-Moon angle: 143.0°

The accuracy of the scale at this angle is a little weak; there is more resolution when the Sun and the Moon are closer together. The Nautical Almanac tables only include positions up until 120° separation, so this particular sight would not even be covered by their tabulations.

However the Observed Lunar Distance is the angle that we saw, affected by refraction. We need to compute the real angle, with the heights corrected for refraction and parallax.

Still using the parallax side, the minutes of the Moon's height can be corrected to add in the parallax -- select the correct HP circle and follow it until the height is reached. The pointer now points to the corrected minutes.

The Sun can be corrected using the normal sun wheel technique.

TODO: show these on the slide rule

- Height of Sun, corrected: 47°12.0' = 47°12.8' - 0.8'

- Height of Moon, corrected: 47°18.8' = 46°42.3' - 0.8' + 37.3'

Now the actual lunar distance can be computed with the navwheel again, using the Sun-Moon angle from above.

- Lunar Distance: 80.12°

To make it easy to interpolate this lunar distance between the two hour measurements in the almanac, first rotate the inner wheel so that it's index points to the number of minutes of the first hour on the outer wheel (59.1'). Then rotate the pointer to the minutes for the start of the next hour on the outer wheel (26.7'). Note where the pointer crosses the end of the curve -- this is the scale factor for the number of minutes per hour that the lunar distance is changing. outer.

Now rotate the pointer to the minutes of the observation (0.12°, which can be read on the outer scale on the outer ring). Locate where the pointer crosses the scale factor line and follow the radial curve to the outside to see that it the result of interpolation is around 17:30 minutes past the hour, which is very close to Frank's measurement of 20:16.

His method requires extensive math and trig precise to several digits using a calculator, while mine can be done with a few spins of the slide rule. Since the slide rule also handles the arithmetic, I find that this is much less error prone -- most of my mistakes are not handling the degree-minute-second math correctly.

The Math

The key part of my method is that the navwheel can compute two specific functions related to spherical triangles for us. The first is given two heights and the distance between them, it will produce the angle for the opposite side of the triangle.

Using the "LHA" technique described on the navwheel page computes the function of the observed lunar distance LD_o and the non-refraction corrected heights H_o^{moon} and H_o^{sun} using the logarithms of the Haversine and Cosines:

Since the correction for the heights only adjusts them up and down, the "LHA" between the Sun and the Moon does not change, so using the navwheel's "H_c" function with the new heights and the already computed LHA produces the angular distance between the two of them.

Because the LHA scale on the reverse of the navwheel is logarithmic, the resolution goes down quite fast as the LD_o becomes large. Additionally the precision of hav(H_o^{moon}-H_o^{sun}) when they are very close together is also quite small. For this reason the technique works best when the distance between the Moon and the star is less than 90° and there is some vertical separation as well.

Source Code

github.com/osresearch/sunwheelmake-moon.py